A Look at AI Image Synthesis

Lying about my vacation with the power of machine learning.

I recently returned home from travelling with friends to Ecuador, the Galapagos, and Costa Rica. Naturally, I filled my phone’s camera roll with many snapshots of the destinations’ scenic vistas and exotic wildlife. I couldn’t wait to amaze my leagues of content-starved Instagram followers with stunning travel photography.

But my followers—loyal and numerous as they are—are not an easily-pleased bunch. With an entire Internet’s worth of content at their fingertips, my photos would have to earn their attention. Amateurish landscape photography just wouldn’t cut it.

Fortunately for me, today there exist AI image synthesis tools like OpenAI’s DALL-E. I upload my photo to their online tool and ask the model to add a “realistic looking sea monster” as well as “an alien UFO.” In just a few keystrokes, even a fool like me can take an ordinary photo and imbue it with otherworldly excitement:

Right: UFOs and sea monster inpainted using DALL-E.

Despite my (admittedly) frivolous use case, image synthesis utilities like DALL-E have real disruptive potential. To an optimist, they are powerful tools that promise to enhance human creativity and drastically reduce the labor that goes into creating artwork. There are already sizable Internet communities devoted to the creation of AI-generated art.

On the other hand, there are legitimate concerns about these tools’ potential for abuse and questions about the legal ownership of their outputs. Fundamental questions are unanswered, and they will only become more important as AI art grows in popularity.

In this blog post, we’ll take a first look at the rapidly developing world of AI image synthesis. We’ll explore how generative AI works, and we’ll discuss what’s promising—and what’s problematic—as new and better tools continue to be developed and released to the public.

How does it work?

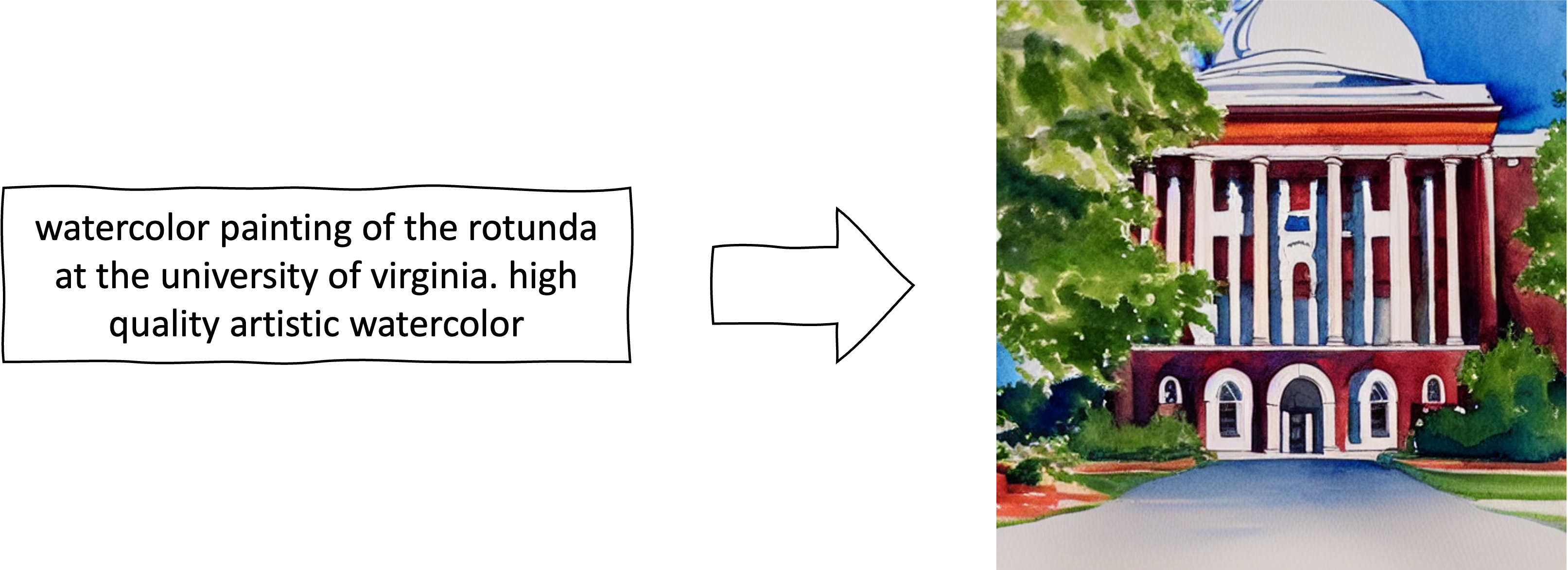

Left: the prompt. Right: output of a Stable Diffusion model.

Most image synthesis models are designed to perform the text to image task: given a text prompt written in natural language, generate a matching image.

All image synthesis models are developed by training deep neural networks on large, labelled datasets. Researchers gather billions1 of images together with natural language captions. At train time, an optimizing algorithm asks the model to generate an image for each caption and pushes it towards outputs that are similar to the corresponding training image.

The specific mechanism to get from prompt to image varies from one model to another. OpenAI’s DALL-E learns an internal, text-like token representation of images that their well-known sequence predictor GPT-3 can understand. Given your prompt, GPT-3 predicts the matching image tokens much like your smartphone’s predictive text, and DALL-E converts them to an image.

GPT-3 is proprietary and training an alternative is prohibitively expensive for most organizations2. Following DALL-E’s release, early open-source techniques like @advadnoun’s The Big Sleep sidestepped this by combining publicly available pre-trained models. Fully trained image generation networks like BigGAN were available, but they weren’t designed to understand natural language prompts. On the other hand, OpenAI’s publicly available CLIP—a model that predicts image captions—understands the relationship between images and language but only generates text. The Big Sleep marries the two: it uses feedback from CLIP to steer BigGAN towards generating images that match closely with the prompt.

Right: Stable Diffusion rendering of the volcano in the ukiyo-e style.

More recently, models like Stability’s Stable Diffusion (open source) and OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 (proprietary) have combined elements of CLIP with iterative diffusion models, a new kind of neural network that begins with a random image and gradually refines it to fit the prompt.

Left: the source image, flowers near Arenal Volcano in Costa Rica.

Right: output of a Stable Diffusion model.

We can also repurpose these models to modify existing images rather than generate new ones outright. Image to image models accept both a source image and text prompt as input. Rather than generate an entirely new image to match the prompt, they merely transform the source image to match. Diffusion models, for instance, can be easily adapted by using the source image (instead of random noise) as a starting point for refinement towards the prompt.

Impressions and the good

Creating images with the help of an AI feels simultaneously empowering and unusual.

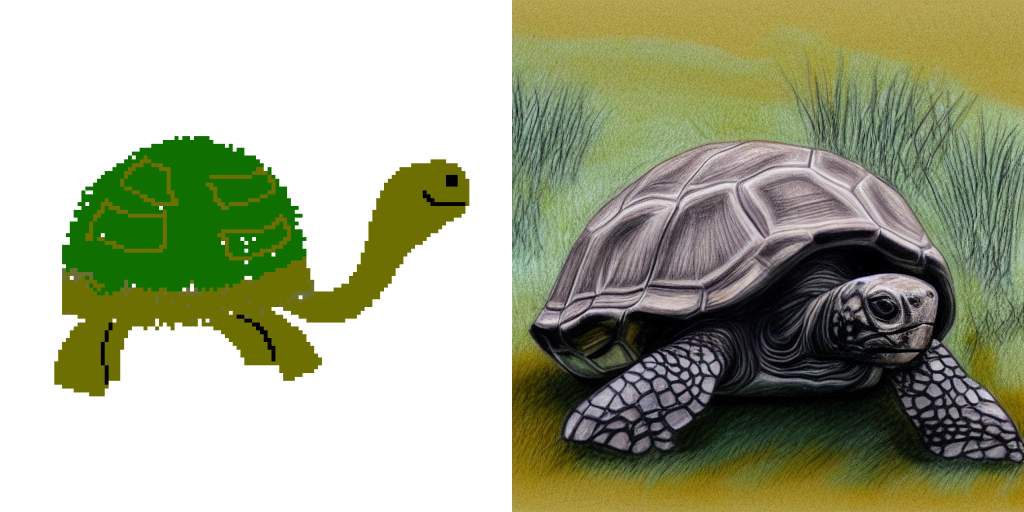

I am not a gifted visual artist. With some patience and careful prompt engineering, Stable Diffusion can execute on a concept much better than I could alone:

Source image: a Galapagos tortoise (not pictured).

In this sense, generative AI unlocks a new kind of expression that I wouldn’t otherwise have access to. It can have a similar effect on visual artists who are capable of realizing their visual concepts using existing tools; creating art can take hours or days. Stable Diffusion runs in under five minutes on my laptop.

There’s also a sense in which working with these tools feels strangely collaborative. I provide a source image and, with the prompt, suggest a general direction to take; however, specific artistic details of the final result are left up to the model. Its outputs can vary substantially even for almost identical prompts.

Right: Stable Diffusion-generated variations on the image attempting to mimic the style of Studio Ghibli.

In practice this means the workflow for generating AI art is highly iterative. You write a prompt and see what the model generates. If you dislike something about the final product, you try to slightly tweak your prompt to correct it. Like collaborating with a human artist, you start by trading ideas and exchanging feedback. After several rounds of trial and error, you hope to converge some kind of shared vision.

OpenAI’s online interface calls DALL-E “your creative copilot,” and I think that’s a fair characterization. AI art is surprising and interesting and highly variable in quality. I rarely get exactly what I’m looking for on the first or even fifth try. Behind every successful AI art piece, I suspect, is a surprising amount of human creative oversight.

It seems to me that these models are most useful as just one part of a larger, human creative process. They can function as dynamic, adaptive sources of inspiration and as effective tools for visual conceptualization.

Questions unanswered and other concerns

The advent of generative AI raises important questions that remain essentially unaddressed. It’s new technology, and we still don’t understand all of the failure modes or potential for abuse. Here, I reflect on a few of the important problems that have been identified3.

Misinformation and deepfakes

A deepfake is a kind of fake, AI-generated media artifact that depicts someone (like a politician or celebrity) doing or saying something that they didn’t in reality. Deepfakes’ rise in prominence is concerning, and it doesn’t take much effort to imagine a more nefarious use of generative AI than adding monsters and aliens to your travel photography.

Purpose-built deepfake models for swapping faces and mimicking voices already exist, but there are legitimate concerns that tools like DALL-E could be used by those seeking to deceive others. A first unfortunate truth is that an increase in the quality of AI-generated images of almost any kind will make it easier for bad actors to create intentionally misleading images like this one:

Companies like OpenAI take efforts to limit their products’ usefulness in disinformation campaigns4. It’s a noble effort, but the technology is out there, so sufficiently motivated (and well-funded) entities can always train their own synthesis models without guardrails. It’s only getting easier to pump out fake content algorithmically. The second unfortunate truth is that our best response is probably to embrace a radical skepticism when consuming media, especially on the Internet.

Harmful bias

It is well established that many AI systems appear to suffer from harmful bias in many of the same ways humans do. Image synthesis models are no exception.

The models are trained to predict the most likely image for a prompt, so they are highly susceptible to biases that appear in the training data. To give a (hardly empirical) illustration, I asked Stable Diffusion to generate “a doctor writing on a clipboard” and “a smiling receptionist in a fancy office photo realistic:”

The results would appear to affirm American race and gender stereotypes. The doctor looks like a white man, while the receptionist looks like a white woman. Presumably, white men (resp. women) are overrepresented among images of doctors (receptionists) in Stable Diffusion’s training dataset.

Correcting for this kind of learned dataset bias is particularly difficult since the entire purpose of a machine learning algorithm is to detect and exploit statistical regularities in its training dataset. To the model, the fact that the doctors it sees are often (but not always) white men is no different from the fact that doctors it sees are often (but not always) wearing lab coats—even though only the second association is meaningful5.

This example illustrates why a diverse training set can be so important. Neural networks will seize upon whatever patterns they can detect; by collecting a wide variety of examples (e.g. doctors of many races and all genders), we make sure the patterns that do exist are actually meaningful.

Intellectual property

So you’ve used an AI to create an awesome piece of artwork. But how can you be sure the model hasn’t inadvertently plagiarized one of its training examples? And who has legal ownership of the model’s output?

Image synthesis tools’ training images are collected by scraping pages on the public Internet6 without regard for how they are licensed. If a model reproduced one of its training examples, a user could unknowingly plagiarize from the original artist. These concerns have already prompted conflict in other domains: for instance, a class-action lawsuit alleges that GitHub Copilot, a code-generating AI with similar architecture to DALL-E, violates the licenses of the public code it was trained on.

Since July 2022, OpenAI has granted DALL-E users full rights to commercialize its outputs. Similarly, Stable Diffusion’s license grants full rights over generations to its users. But even still, the US Copyright Office has ruled that AI-generated content lacks “human authorship” and cannot be protected by copyright law.

Users of AI image synthesis tools should keep in mind that the relationship between a model’s training inputs and output image are complicated and not always well-understood. Even if you are permitted to monetize the outputs of a model, keep in mind that the intellectual property implications are fraught with unanswered questions.

Conclusion

We’re at an exciting time for AI. It feels like we’re seeing generative breakthroughs (most recently, ChatGPT) almost every month, and there is no shortage of excited, clever people ready to explore what is possible with these new technologies.

Image synthesis models have achieved impressive results at a rapid rate of development. For the particularly exploratory creative, I believe these tools have already shown their potential as part of the design process. But all users—and particularly those who seek to commercialize AI creations—should be wary of the risks, legal and otherwise. Like many other disruptive emerging technologies, AI image synthesis models can improve faster than the rest of us can reckon with the consequences.

Appendix A: The AI Art Scene

Are you interested in seeing others’ AI-generated artwork or perhaps making some of your own? There are large online groups dedicated to discussing and sharing AI art. A few resources I’m aware of:

- r/aiArt on Reddit

- Midjourney’s community on Discord

- Berkeley machine learning blogger Charlie Snell’s list of notable AI art Twitter accounts

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Jefferson Scholars Foundation’s independent travel stipend for making my trip to Latin America possible.

References

- Charlie Snell’s Alien Dreams: An Emerging Art Scene blog post.

- Charlie Snell’s DALL-E Explained series.

- Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation, the whitepaper for DALL-E.

- Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents, the whitepaper for DALL-E 2.

- High Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models, the whitepaper for Stable Diffusion.

- Jay Alammar’s The Illustrated Stable Diffusion.

Tools I used to generate images for this post:

- OpenAI’s online tool for editing photos with DALL-E.

- DiffusionBee, a free and open-source desktop interface for Stable Diffusion.

Footnotes

-

Stable Diffusion was trained on laion2B-EN, a dataset consisting of over two billion labelled images. ↩

-

In their paper, Brown et al. note that their largest model required 3,640 petaflop/s-days to train, or 3,640 days of continuous work for a single computer performing \(10^{15}\) floating point operations per second. ↩

-

For a more comprehensive review of some of the anticipated risks of image synthesis models, see OpenAI’s review of the risks identified for DALL-E 2. ↩

-

DALL-E 2 is deliberately configured to forget faces in its training data, but researchers note that this approach isn’t bulletproof. ↩

-

For a neat visual demonstration of a neural network learning an unintended association, see the dumbbell example in this Google blog post. ↩

-

For instance, Stable Diffusion’s LAION is generated from the comprehensive Common Crawl. ↩