Solving NYT Pips with SMT

SMT solvers are neat and friendly.

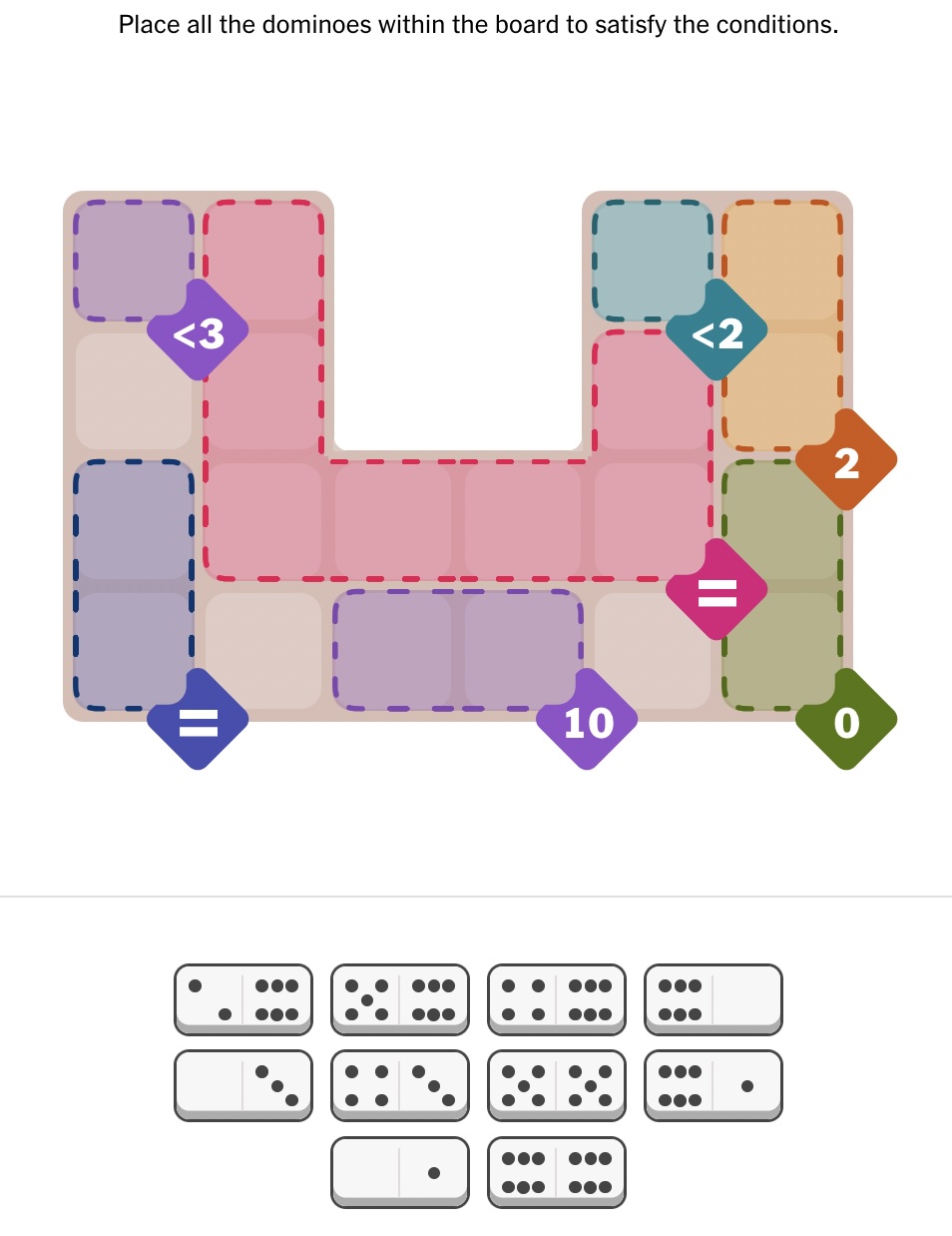

The New York Times recently released a game called Pips:

The goal is to fill the board with dominoes such that each of the conditions are met:

- < k – Sum of values in region is less than k.

- > k – Sum of values in region is greater than k.

- k – Sum of values in region equals k.

- = – Each value in region is the same.

- ≠ – Each value in region is distinct.

I like solving puzzles, but for some reason I prefer sucking all the joy out of them by writing computer programs that solve them for me.

And recently, I’ve been playing around with the Z3 theorem prover from Microsoft Research. Z3 is a satisfiability modulo theories (SMT) solver. SMT generalizes the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT) to more complicated formulas involving objects like the reals and the integers.

You can use Z3 to solve all kinds of interesting constraint satisfaction problems. I had previously read and enjoyed an article from Hillel Wayne about solving the LinkedIn Queens puzzle using Z3. So when I heard about Pips, I decided to try my hand at writing a solver.

You can interact with Z3 using a variety of languages. I’m comfortable with Python, so I chose Z3Py.

Reading input

This is definitely the least interesting part. But you might like to know that the NYT games expose remarkably straightforward API endpoints.

% curl https://www.nytimes.com/svc/pips/v1/2025-08-24.json 2>/dev/null | jq

{

"printDate": "2025-08-24",

"editor": "Ian Livengood",

"easy": {

"id": 188,

"constructors": "Rodolfo Kurchan",

"dominoes": [[0, 4], /* ... */],

"regions": [

{

"indices": [[1,0]],

"type": "sum",

"target": 6

},

/* ... */

]

},

/* ... */

}

For convenience, we define some dataclasses.

# (left tile value, right tile value)

Domino = tuple[int, int]

# (row, col)

Cell = tuple[int, int]

class Constraint(Enum):

empty = "empty"

sum = "sum"

equals = "equals"

unequal = "unequal"

less = "less"

greater = "greater"

@dataclass

class Region:

cells: list[Cell]

constraint: Constraint

target: int | None

@dataclass

class Puzzle:

dominoes: list[Domino]

regions: list[Region]

I won’t cover the deserializers here, but you can find them on GitHub.

Encoding in SMT

Most of our work lies in encoding the puzzle in a way Z3 can understand. This took me a couple of tries to get right, but I settled on the following approach:

- Break the dominoes in half. Treat each half-domino as an independent “tile.” This lets us avoid thinking too much about rotation. Later, we’ll add constraints that ensure tiles are laid out in a physically plausible way.

- Maintain two grids. The solution consists of two m by n integer matrices,

cell_tilesandcell_values.cell_tiles[i][j]represents the id of the tile located at (i, j).cell_values[i][j]represents the numerical value of the tile located at (i, j).- We’ll add constraints that ensure these two matrices agree with each other.

After setting things up this way, you’ll see that we can express the puzzle’s constraints naturally.

First, we set up the solver and initialize our grids.

s = Solver()

m, n = puzzle.size()

num_tiles = 2 * len(puzzle.dominoes)

def in_bounds(i, j):

return 0 <= i < m and 0 <= j < n

cell_tiles = [ [ Int(f"cd_{i}_{j}") for j in range(n) ] for i in range(m) ]

cell_values = [ [ Int(f"cv_{i}_{j}") for j in range(n) ] for i in range(m) ]

We also populate a dict that maps each cell to its corresponding region.

cell_to_region = {}

for region in puzzle.regions:

for cell in region.cells:

cell_to_region[cell] = region

Now we can begin emitting constraints.

for i in range(m):

for j in range(n):

ct = cell_tiles[i][j]

cv = cell_values[i][j]

# If the cell is outside of any region, no tiles can be placed here.

if (i,j) not in cell_to_region:

s.add(ct == -1)

s.add(cv == -1)

continue

# Let's consider assigning each tile.

s.add(0 <= ct, ct < num_tiles)

for tid in range(num_tiles):

# If tid is assigned to this cell:

# 1. Cell's value must match tile's value.

# 2. Exactly one neighbor must be the sibling tile.

# Precondition

is_assigned = ct == tid

# Requirement 1

val_matches = cv == puzzle.dominoes[tid // 2][tid % 2]

# Requirement 2

sibling_tid = tid ^ 1

neighbors = [ (i, j+1), (i+1, j), (i, j-1), (i-1, j) ]

in_bounds_neighbors = [ (k,l) for k,l in neighbors if in_bounds(k, l) ]

num_sibling_neighbors = [ (cell_tiles[k][l] == sibling_tid, 1) for (k,l) in in_bounds_neighbors ]

exactly_one_sibling_neighbor = PbEq(num_sibling_neighbors, 1)

s.add(Implies(is_assigned, And(val_matches, exactly_one_sibling_neighbor)))

We index dominoes and tiles like so:

- domino 0 consists of tiles 0, 1,

- domino 1 consists of tiles 2, 3,

- …

- domino n consists of tiles 2n, 2n+1,

This is useful because it makes it easy to convert between domino IDs and tile IDs:

tid’s domino ID istid // 2.tid’s index within a domino istid % 2.tid’s sibling tile ID can be computed by flipping the least significant bit (LSB) using XOR,tid ^ 1.- If

tidis even, then its LSB is 0, andtid ^ 1 == tid + 1. - If

tidis odd, then its LSB is 1, andtid ^ 1 == tid - 1.

- If

Requirement 1 enforces that cell_tiles and cell_values agree with each other. It forces the cell value to match the assigned tile.

Requirement 2 uses a pseudo-Boolean constraint to ensure that exactly one neighbor is the sibling tile. Imagine representing each Boolean value as a zero or one and computing a linear combination. Pythonically:

num_sibling_neighbors = ( int(east_is_neighbor) * 1 +

int(south_is_neighbor) * 1 +

int(west_is_neighbor) * 1 +

int(north_is_neighbor) * 1 )

add_constraint(num_sibling_neighbors == 1)

This forces each tile to be directly adjacent to its sibling, which has the effect of allowing us to place dominoes with rotation.

We add constraints ensuring each tile is used exactly once, again using pseudo-boolean constraints.

# For each tile...

for tid in range(num_tiles):

preds = []

for i in range(m):

for j in range(n):

preds.append((cell_tiles[i][j] == tid, 1))

# ...exactly one cell can have this tile assigned.

s.add(PbEq(preds, 1))

At this point, we have encoded all the rules governing how dominoes can be placed on the board. All that’s left is to emit the constraints specified by the puzzle itself. Luckily, it’s now straightforward.

for r, region in enumerate(puzzle.regions):

if region.constraint == Constraint.empty:

# empty constraint: just need to place a tile here.

for i, j in region.cells:

s.add(cell_tiles[i][j] != -1)

elif region.constraint == Constraint.equals:

# equals constraint: each tile must equal some value, k.

k = Int(f"k_{r}")

for i, j in region.cells:

s.add(cell_values[i][j] == k)

elif region.constraint == Constraint.unequal:

# unequal constraint: each tile must be distinct.

s.add(Distinct(cell_values[i][j] for i,j in region.cells))

else:

# sum, less, greater constraints: region total must satisfy constraint

total = Sum(cell_values[i][j] for i,j in region.cells)

target = region.target

if region.constraint == Constraint.less:

s.add(total < target)

elif region.constraint == Constraint.sum:

s.add(total == target)

else:

s.add(total > target)

Solving the puzzle

All that’s left is to invoke the solver and print out its solution!

result = s.check()

if str(result) != "sat":

raise RuntimeError(f"Solver returned {result}!")

model = s.model()

for i in range(m):

for j in range(n):

v = model.evaluate(cell_values[i][j]).as_long()

t = model.evaluate(cell_tiles[i][j]).as_long()

# if the tile to my right belongs to a different domino, separate us with a vertical pipe

# this makes the ASCII output slightly easier to read :)

next_different = False

if j < n - 1:

t_next = model.evaluate(cell_tiles[i][j+1]).as_long()

if (t // 2) != (t_next // 2):

next_different = True

ch = v if v >= 0 else "-"

print(ch, end="|" if next_different else " ")

print()

% uv run python3 main.py 2025-08-24 hard

1 6|- -|1 0

5 6|- -|6 2

4 6|6 6|6 0

4 3|5 5|3 0

SMT solvers are really cool

In general, SMT is a really difficult problem for computers to solve. SAT is an (really, the) NP-hard problem, and our formulation of SMT is no easier (you can solve SAT using an SMT solver). But computational complexity aside, industrial SMT solvers like Z3 are really good at solving tons of practical problems.

And it’s not just logic puzzles. I first heard about Z3 in the context of formal verification. There, SMT solvers are commonly used to verify properties of program behavior. To name just one example, the Verus framework uses Z3 to check assertions about real-world Rust code. The high-level idea here is to convert your program into an SMT formula whose (un-)satisfiability implies the validity of your assertions1.

To quote another article, SAT solvers are “fast, neat, and underused.” I would say this holds for SMT solvers too, but:

- I can’t speak for their speed (except that it’s good enough for Pips),

- and they seem to be getting quite a bit of use.

What I can say:

- SMT solvers are neat

- SMT is a considerably friendlier interface than SAT for modeling problems like this one.

So there you have it: SMT solvers are neat and friendly.