Building a WORDLE Solver in Python

Exploits of a coder in quarantine.

(Updated 1/17/2022. View this post’s history on GitHub.)

I spent the first days of a fresh new year like many others: in quarantine with COVID. Fortunately I had already received my vaccine and booster; my symptoms were mild. But I was still left with an abundance of downtime before classes began, and I became completely preoccupied with the delightful WORDLE.

For the uninitiated, WORDLE is an online word game similar to the guessing game Mastermind. In WORDLE, you get six attempts at guessing a secret five-letter word. After each guess, you get feedback on which letters you have guessed correctly and in the correct position (highlighted in green), which you have guessed correctly but are misplaced (yellow), and which do not appear at all in the puzzle’s solution. You can use this feedback to hone in on the correct solution.

I love WORDLE. Its origin story is downright adorable. Cursory research suggests I am not WORDLE’s only admirer; you can find WORDLE scores peppering your Twitter feed, and it has produced some great technical analysis and spin-offs.

And so, for the inaugural post on my blog, I aim to contribute to the ongoing Cambrian explosion of WORDLE programming posts by building a WORDLE solver in Python.

Strategy overview

Our strategy is adapted from computer scientist Donald Knuth’s strategy for solving Mastermind. Our strategy is to maintain a list of candidate solutions—words which could possibly be the answer to a given puzzle. At each step, we make a guess, and based on the feedback, we narrow the space of viable candidate solutions.

WORDLE has two wordlists. One is a list of the valid guesses, which contains 10,657 words at present. The other is a list of 2,315 possible puzzle solutions. Presumably these are separated so that no WORDLE requires knowledge of a rare or obscure word to solve. We’ll load both lists and initialize a list of possible guesses and possible solutions.

def load_words(wordlist_path: str) -> typing.List[str]:

"""Loads wordlist from a newline-delimited file."""

with open(wordlist_path, "r") as f:

return [line.strip() for line in f.readlines()]

if __name__ == "__main__":

all_solutions = load_words("./solutions.txt") # load possible solution words

all_guesses = solutions + load_words("./guesses.txt") # load additional guess words

# each solution word is itself a valid guess word.

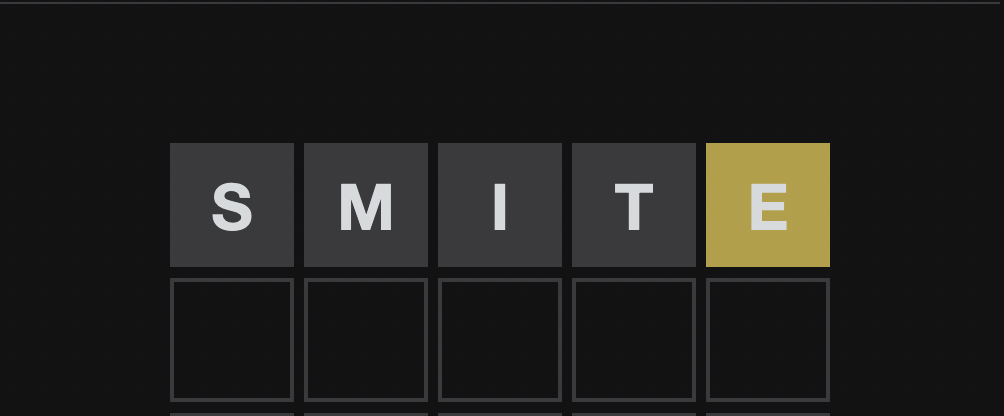

After we make a guess, we need to infer from the feedback which candidate solutions remain valid. Suppose we guess the word “SWORD” and see the following feedback.

We can cut any candidate solution that doesn’t have R in the fourth position. We can also discard any candidate containing the letters S, W, O, or D, since they are gray.

Yellow letters give us information, too. We can toss out any candidate words without Es. Also, the fact that E is yellow (rather than green) means the solution doesn’t have an E in the fifth position, so we can discard any candidate words with E in the fifth position.

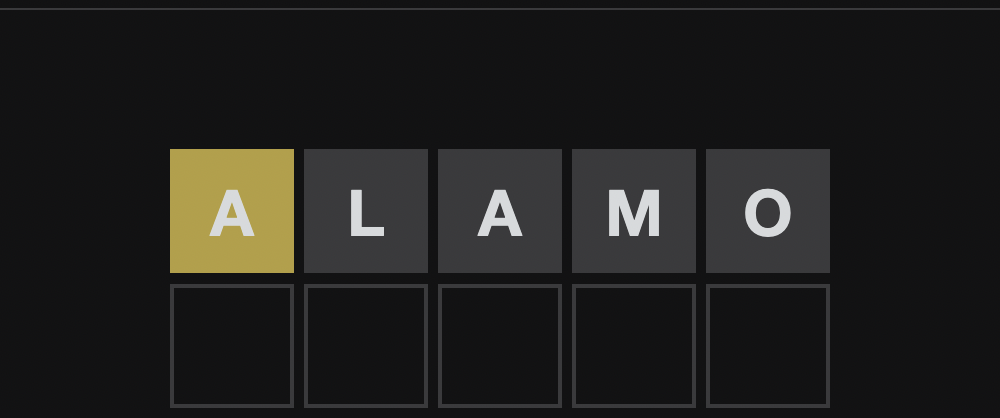

Accounting for possible repetition requires a bit more thinking. In the following picture, the solution is PANIC:

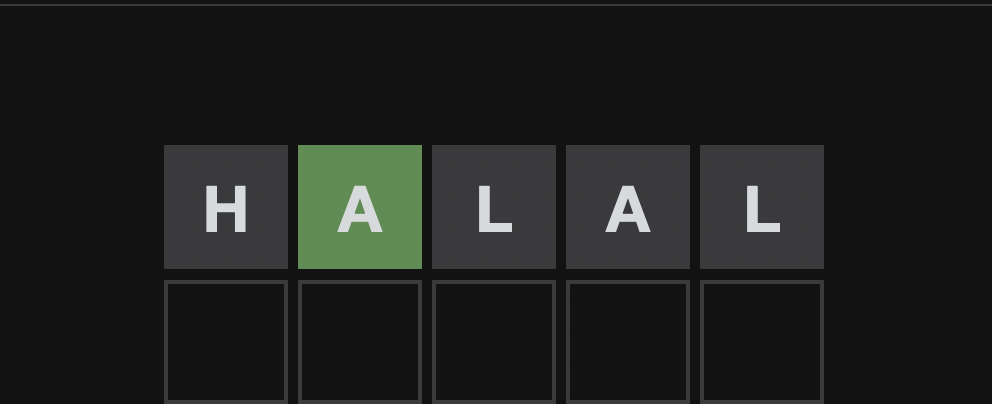

The first A is yellow, but the second one is gray because PANIC only contains one A. If we had instead guessed HALAL:

The second A is still gray. Each yellow/green letter in our guess “uses up” a corresponding letter in the solution; if we run out, further repetitions in our guess are gray, even though the letter happens to be in the solution. For non-repeated letters, gray means the letter is not in the word at all. As the example above shows, this is not necessarily the case for repeated letters.

word_consistent predicate generator

We express this logic as a function, word_consistent, which accepts feedback about a guess and returns a predicate that checks whether a given word is consistent with the feedback.

First, we introduce a type alias to make our type hints a little more readable. PositionLetterPair is a tuple (int, str) representing a letter at a given position. (So (0, "g") represents a G in the first position.)

# type alias for pair of (int, str)

# (p, l) represents a letter l in position p

PositionLetterPair = typing.Tuple[int, str]

Now we define word_consistent, which accepts

green_pairs, a list of position-letter pairs representing the green lettersyellow_pairs, a list of position-letter pairs representing the yellow lettersgray_pairs, a list of position-letter pairs representing the gray letters

It returns a function, referred to internally as pred, which is a predicate on strings: it accepts string objects and returns a boolean value. The idea of a function that returns another function might seem a little bit strange, but we’ll see later why this is a surprisingly elegant way of doing things.

def word_consistent(green_pairs: typing.List[PositionLetterPair],

yellow_pairs: typing.List[PositionLetterPair],

gray_pairs: typing.List[PositionLetterPair]) -> typing.Callable[[str], bool]:

"""Returns a predicate testing whether a given word is consistent with observed feedback."""

def pred(word):

# count the letters in word

letter_counts = collections.Counter()

for letter in word:

letter_counts[letter] += 1

# any viable solution must:

# have letter l at position p for any green pair (p, l)

for (p, l) in green_pairs:

if word[p] != l:

# green pair does not match

return False

else:

# green letters "use up" one of the solution letters

letter_counts[l] -= 1

# not have letter l at position p for any yellow pair (p, l)

for (p, l) in yellow_pairs:

if word[p] == l:

# letter does match, but it shouldn't

return False

else: # ...and contain letter l somewhere, aside from a green space

# doesn't contain this letter,

# or perhaps doesn't contain it enough times

if letter_counts[l] <= 0:

return False

else:

# yellow letters "use up" one of the solution letters

letter_counts[l] -= 1

# contain no gray letters in excess (not "used up")

for (p, l) in gray_pairs:

if letter_counts[l] != 0:

return False

return True

return pred

Choosing a guess

We now need to establish a mechanism for deciding which candidate word to guess at any given point. That is, we need a decision rule: an algorithm for determining which action to take given our prior observations.

Intuitively, we want to always guess the word that cuts down the set of candidate solutions as much as possible. Discovering this word is not straightforward, however, because the feedback we receive on a word is a function of both our guess and the unknown solution to the puzzle. (To illustrate: you can cut down the set of candidates significantly more by guessing SMITE when the solution is SMITH than you can when the solution is FOCAL.)

Fortunately, decision rules like minimax exist to make decisions in spite of this uncertainty. Minimax instructs us to guess a word that minimizes the maximum possible loss in any outcome. For any guess, it asks, “how many words would be left in the worst-case scenario?” and picks the word that minimizes this quantity.

Exploitation vs. exploration

Anyone who has played enough WORDLE has doubtless encountered the tradeoff between exploitation and exploration. At every step, you have information about which solutions are valid. You can choose to exploit this information, making guesses and attempting to win the puzzle completely. But you might instead choose to explore: make guesses that cannot possibly be the puzzle solution but instead yield more information.

For instance: once you see a green letter, you know the solution contains that exact letter at that exact position. On your next guess, you might guess a different letter in that space to see if it is present in the word at all. You do this even though disregarding the green letter guarantees your next guess will not solve the puzzle; you have chosen to explore rather than exploit.

This decision rule will always choose to explore. The list of possible guesses is populated with the union of the two wordlists and is never altered afterwards. What this means in practice is that the chosen guess might not even be a viable solution; it is just the word that will cut down the set of possible solutions the most (in the worst-case scenario.)

Generating feedback

Before we implement our minimax decision rule, we have to generate the feedback from guessing a word under a given solution. That’s what generate_feedback does; you give it a puzzle solution and your guess, and it returns:

- the list of

PositionLetterPairs representing to the green letters, - the list of

PositionLetterPairs representing to the yellow letters, - and the list of

PositionLetterPairs representing to the gray letters.

def generate_feedback(soln: str, guess: str) -> typing.Tuple[typing.List[PositionLetterPair],

typing.List[PositionLetterPair],

typing.List[PositionLetterPair]]:

"""Returns the feedback from guessing `guess` when the solution is `soln`.

The feedback is returned as a tuple of (green (pos, letter) pairs, yellow (pos, letter) pairs, set of gray letters)

"""

# sanity check

assert len(soln) == len(guess)

# counts all the letters in the solution word

letter_counts = collections.Counter()

for letter in soln:

letter_counts[letter] += 1

# selects all (position, letter) pairs where the letters in soln and guess are equal

green_pairs = [(p1, soln_letter) for ((p1, soln_letter), guess_letter)

in zip(enumerate(soln), guess) if soln_letter == guess_letter]

# subtract the green letters from the letter counts,

# since green letters "use up" letters from the solution word.

for (_, letter) in green_pairs:

letter_counts[letter] -= 1

yellow_pairs = []

for pos, letter in enumerate(guess):

# there are excess letters that aren't already marked green

if letter_counts[letter] > 0 and (pos, letter) not in green_pairs:

# append this pair

yellow_pairs.append((pos, letter))

# subtract one from excess letter count; yellow letters "use up" solution word letters.

letter_counts[letter] -= 1

# all remaining pairs are gray

gray_pairs = [pair for pair in enumerate(guess) if pair not in green_pairs and pair not in yellow_pairs]

return green_pairs, yellow_pairs, gray_pairs

We can use this method to determine how many candidate words we get to slash for each possible guess under each possible solution. We also get to use some snazzy Python features for the promised ergonomic payoff:

- Unpacking operator: We get to use the unpacking operator

*to pass the result ofgenerate_feedbackdirectly as arguments toword_consistent. - First-class functions: We get to use the predicate returned by

word_consistentin afilterover candidate words.

def select_guess(guesses: typing.List[str],

candidates: typing.List[str]) -> typing.Tuple[str, int]:

"""Selects a guess based on minimax decision rule.

Returns tuple of (word, max), where word is the guess, and max is

the maximum possible of remaining candidates after guessing `word`.

"""

current_minimax = None

current_minimax_word = None

print(f"Selecting best guess from {len(guesses)} possibilities...")

for guess in guesses:

# max loss for this guess

maximum_remaining = None

for possible_soln in candidates:

# feedback guessing `guess` when the solution is `soln`

feedback = generate_feedback(possible_soln, guess)

# how many words remain after incorporating this feedback

remaining = len(list(filter(word_consistent(*feedback), candidates)))

# is this a new maximum loss?

if maximum_remaining is None or remaining > maximum_remaining:

maximum_remaining = remaining

if current_minimax is not None and maximum_remaining > current_minimax:

# the maximum for this guess is larger than the current minimax

# not possible that this word represents a minimax, we can break early

break

if current_minimax is None or maximum_remaining < current_minimax:

current_minimax = maximum_remaining

current_minimax_word = guess

return current_minimax_word, current_minimax

The worst-case runtime complexity of selecting a guess is cubic in the size of the wordlist, since it has to loop over all candidate words

- once for each possible guess,

- once for each possible solution,

- and once to filter each candidate. (This is obscured by the

filter.)

- and once to filter each candidate. (This is obscured by the

- once for each possible solution,

Fortunately, we rarely encounter the worst-case: because we are searching for a “minimum of maximums”, we can break the inner loop if the running maximum ever goes above the running minimax. Even with this optimization, selecting the first guess takes around ~3 minutes on my laptop.

At this point, the algorithm suffices to tell us the best starting word according to our decision rule.

if __name__ == "__main__":

all_solutions = load_words("./solutions.txt") # load possible solution words

all_guesses = all_solutions + load_words("./guesses.txt") # load additional guess words

# each solution word is itself a valid guess word.

guess, worst_case = select_guess(all_guesses, all_solutions)

print(f"I suggest: {guess.upper()}, which leaves {worst_case} words at worst")

Which outputs:

Selecting best guess from 12972 possibilities...

I suggest: ARISE, which leaves 168 words at worst

This is exactly in line with the suggested starting words at wordlesolver.com. (WordleSolver suggests multiple words—all of which are anagrams of ARISE.) It differs from the suggested SOARE on Matt Rickard’s blog, but Matt’s article filters by average performance over all possible solutions, rather than worst-case performance, like ours does.

Handling user input

The last thing we have to do to convert this into a fully-fledged solver is to setup an input loop. At each step, it:

- Selects a guess from the candidates,

- prompts the user for feedback from their WORDLE game,

- and narrows down the candidates based on their selection.

This implementation’s input method is a little bit clunky; it asks users to enter green, yellow, and gray tiles one line at a time, entering _ for blanks. It also hard-codes the first guess, since the solver always suggests ARISE.

One interesting advantage of this approach is that you don’t have to enter the guesses suggested by the solver. If you are halfway through an existing game and you want the solver to try its best to save you, you can just enter the results of your previous guesses and let it take over.

if __name__ == "__main__":

all_solutions = load_words("./solutions.txt") # load possible solution words

all_guesses = all_solutions + load_words("./guesses.txt") # load additional guess words

# initialize space of candidates to all puzzle solutions

candidates = all_solutions

for i in range(6):

if i > 0:

guess, worst_case = select_guess(all_guesses, candidates)

else:

# hard-code first guess to save on processing time

guess, worst_case = "arise", 168

print(f"I suggest: {guess.upper()}, which leaves {worst_case} words at worst")

input_green = input("Enter the green letters, using _ for blanks: ")

assert len(input_green) == 5

green_pairs = [

(position, letter.lower()) for (position, letter) in enumerate(input_green) if letter.isalpha()

]

input_yellow = input("Enter the yellow letters, using _ for blanks: ")

assert len(input_yellow) == 5

yellow_pairs = [

(position, letter.lower()) for (position, letter) in enumerate(input_yellow) if letter.isalpha()

]

input_gray = input("Enter the gray letters, using _ for blanks: ")

assert len(input_gray) == 5

gray_pairs = [

(position, letter.lower()) for (position, letter) in enumerate(input_gray) if letter.isalpha()

]

pred = word_consistent(green_pairs, yellow_pairs, gray_pairs)

candidates = list(filter(pred, candidates))

if len(candidates) == 1:

print("The word is:", candidates[0].upper())

break

elif len(candidates) < 1:

print("The puzzle is impossible! Perhaps you entered results incorrectly?")

break

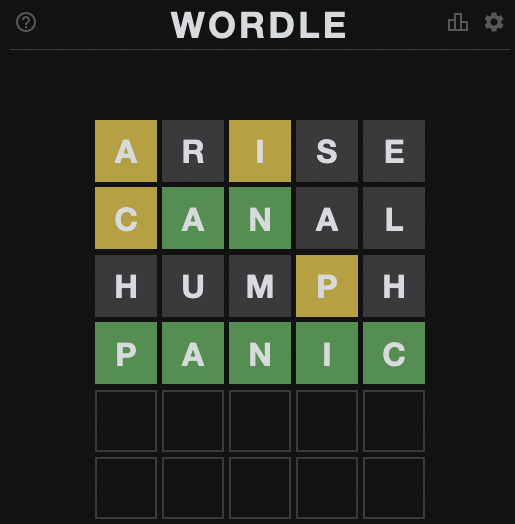

Demonstration

Let’s use our new solver to crack today’s WORDLE:

I suggest: ARISE, which leaves 168 words at worst

Enter the green letters, using _ for blanks: _____

Enter the yellow letters, using _ for blanks: a_i__

Enter the gray letters, using _ for blanks: _r_se

Selecting best guess from 12972 possibilities...

I suggest: CANAL, which leaves 4 words at worst

Enter the green letters, using _ for blanks: _an__

Enter the yellow letters, using _ for blanks: c____

Enter the gray letters, using _ for blanks: ___al

Selecting best guess from 12972 possibilities...

I suggest: HUMPH, which leaves 1 words at worst

Enter the green letters, using _ for blanks: _____

Enter the yellow letters, using _ for blanks: ___p_

Enter the gray letters, using _ for blanks: hum_h

The word is: PANIC

Success!!

Source code

All of the code for this blog post can be found in the joek13/wordle GitHub repository.

References

Each of the following articles was helpful in writing this post: